Documenting the Meaning of Public Usable* Space with Story-telling Methodologies in Tandale, Dar es Salaam

By Linda Heiß **

This article is based on findings from fieldwork conducted in the frame of a master thesis in the MSc. Integrated Urbanism and Sustainable Design at the University of Stuttgart, submitted in April 2022 with the title: “Stories Behind Places: The Significance of Public Usable Space for Residents of Informal Settlements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania“

WHY document the meaning of urban space?

Most cities’ atmosphere is characterized by their public spaces – their parks, plazas, promenades or waterfronts. These are the open spaces where residents spend their free time, come to relax, socialize, exercise and clear their minds. At least that was my first association when thinking of open public spaces as a person who grew up in Central Europe.

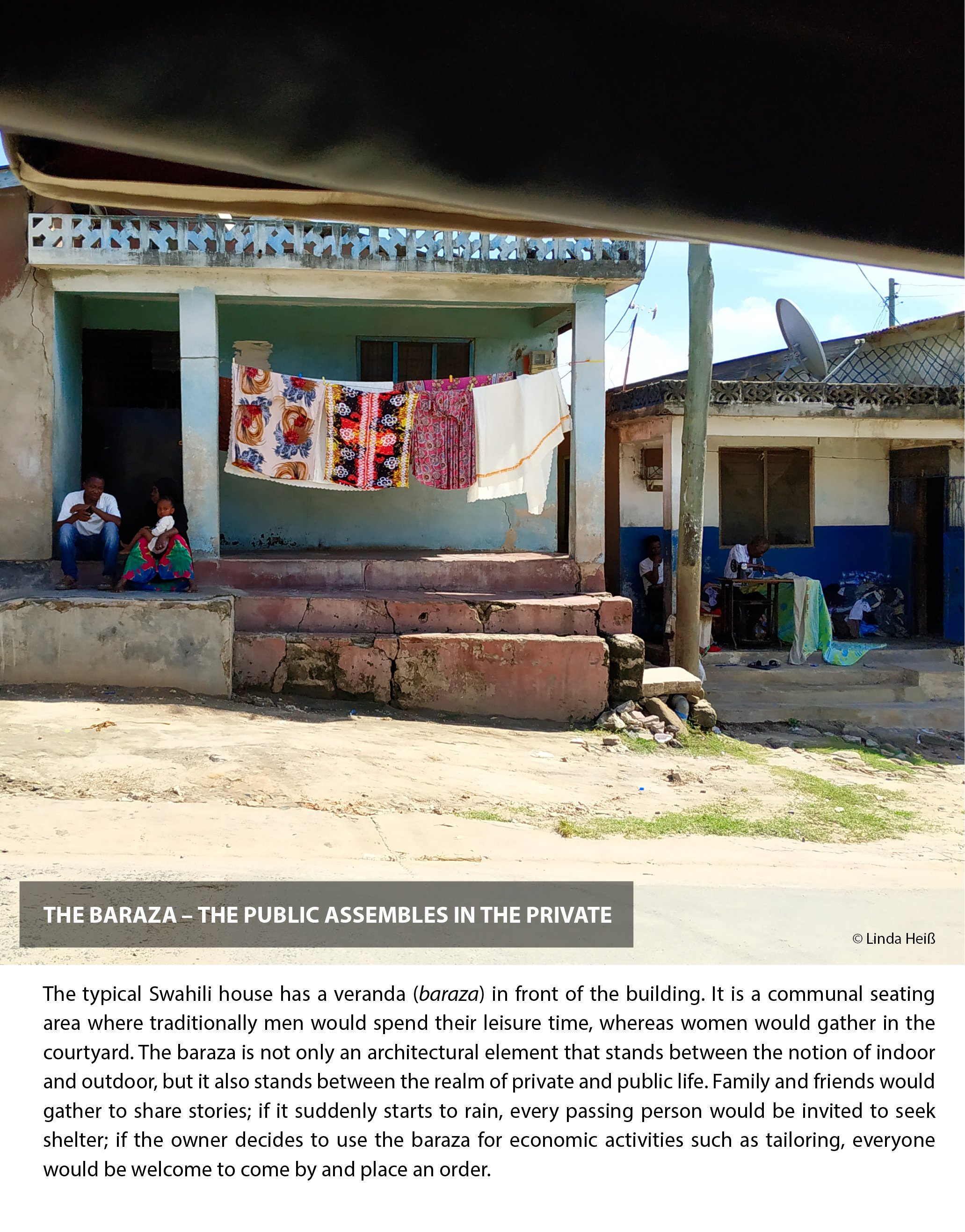

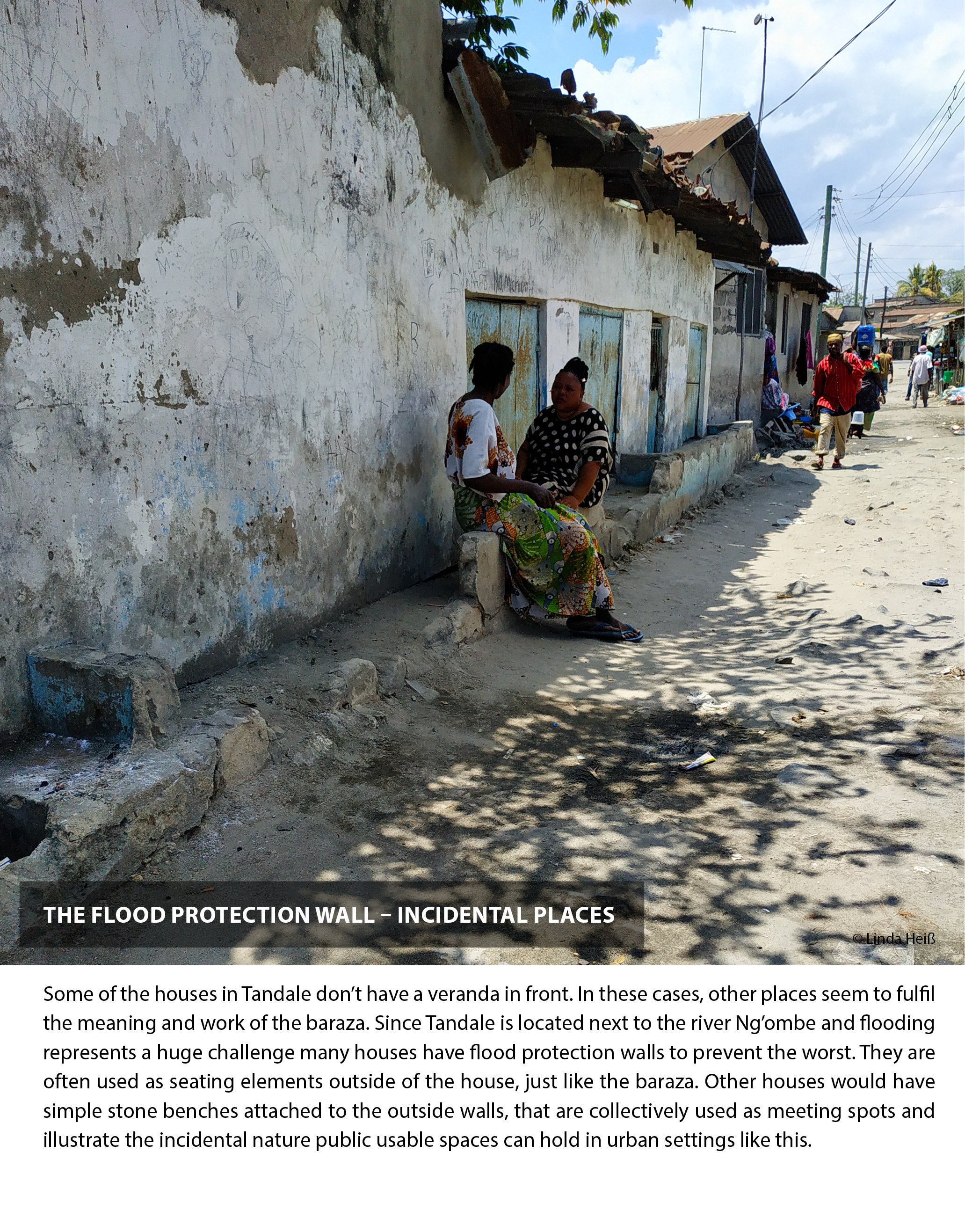

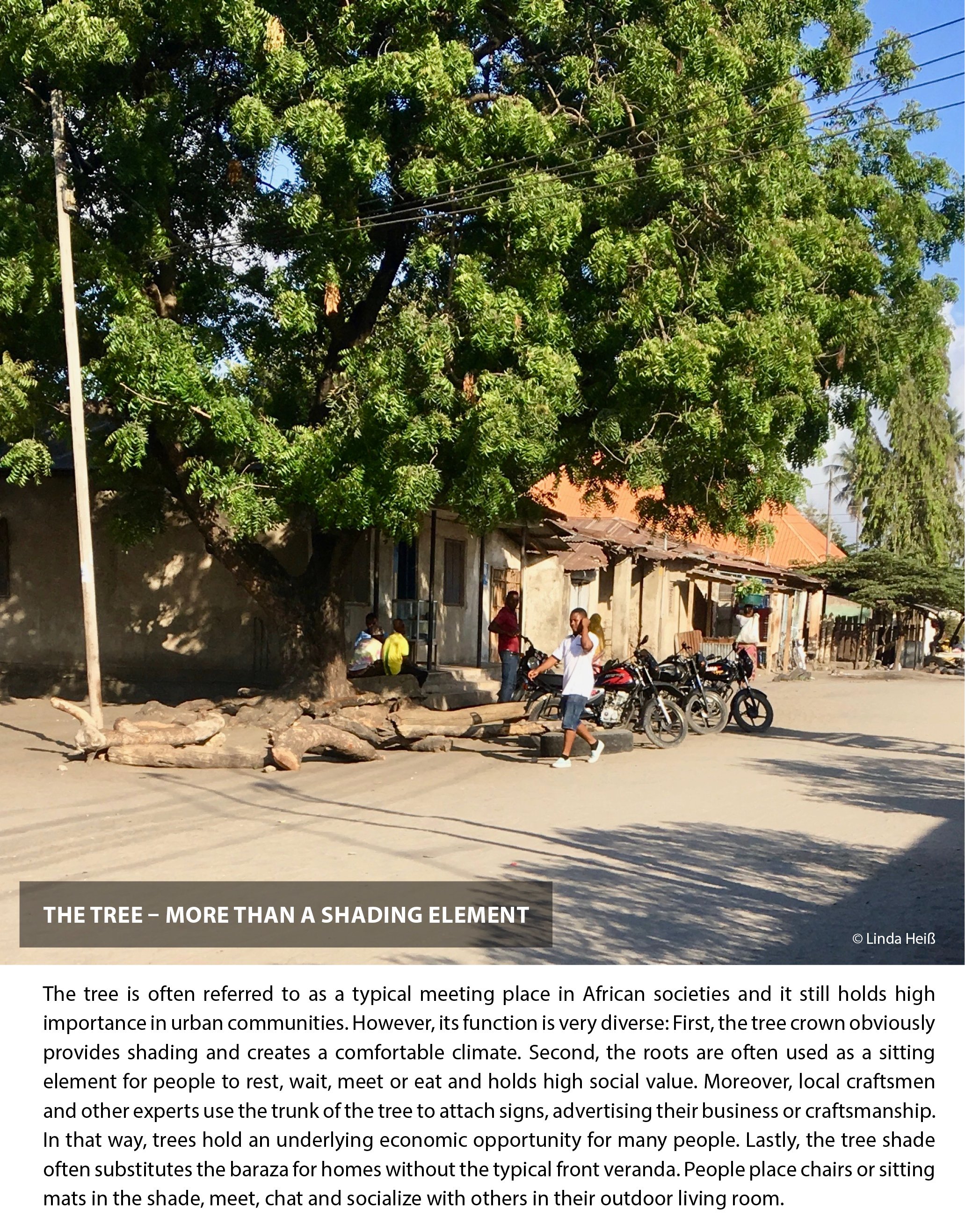

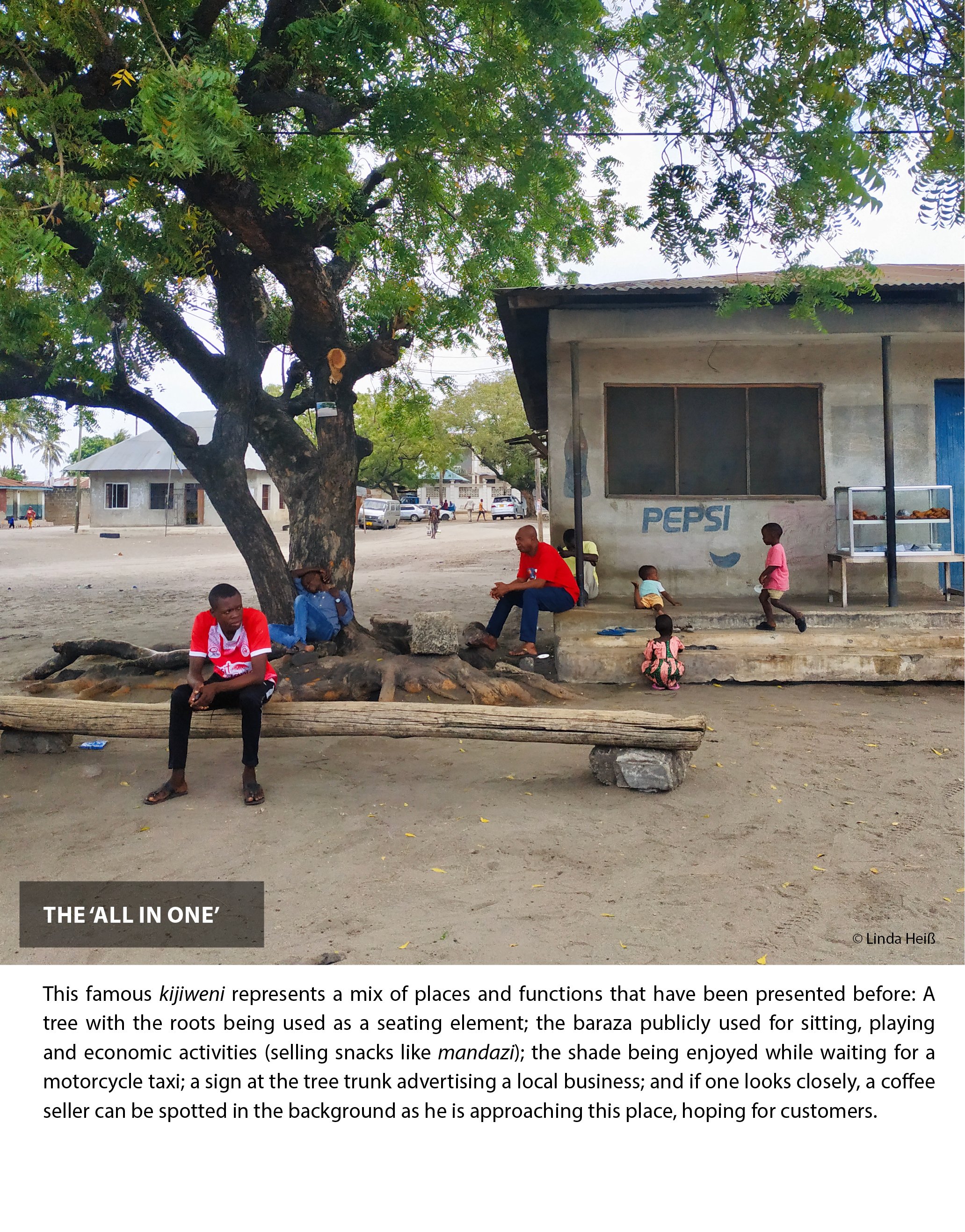

Studying public spaces in the context of Dar es Salaam, however, changed my own definition, understanding and appreciation of those special places. Especially in low-income and densely populated areas, so-called informal settlements, like the case study area of Tandale, any space left-over by houses and roads has the potential to be turned into a meaningful place. Through self-appropriation, inhabitants transform these urban in-between spaces according to their daily needs, they are thus often of temporary nature. In neighbourhoods like Tandale, diverse types of public usable space has to be recognised, as they do not come in parks or squares equipped with seating options. Space dimensions vary as they are shaped by changing activities and everyday practices. These everyday places are not shown in maps and drawings, they do not exist in the minds of planners and decision-makers. They are easily overlooked and forgotten, yet are essential to many people’s lives in different ways. It is the work of urban planners to build a bridge, facilitate between actors and visualise knowledge gaps. Thus, a first step to protecting public space in informal areas is to document the kind of spaces that exist and unravel their meaning for the residents. This might help planners, residents and decision-makers to protect them from further encroachment, and facilitate their continuation.

WHY use story-telling methodologies?

As Vanessa Watson pointed out, “planning research needs to return to the concrete, to the empirical and to case research, not as a mindless return to empiricism, but as a way of gaining a better understanding of the nature of difference and generating ideas and propositions which can more adequately inform practice” (Watson, 2003).

Current planning decisions are often based on instrumental approaches. Top-down approaches and the focus on master plans oftentimes leave little space for residents’ participation. Telling and listening to stories, however, might help us to acknowledge diverse perspectives since „stories play an exceptionally important role in how people assign value to a place” (Cilliers, 2015). Thus, at the centre of this study stood an ethnographic research approach, which can be understood as a branch of anthropology where the researcher fully immerses in real-life environment. It enabled me to produce a narrative of personal perceptions against a theoretical backdrop.

To outsiders, at a first glance and maybe due to their physical appearance or a lack of permanent structures some spaces might not seem to hold a significant value. But often it is the intangible moments that impact people’s lives. Listening to the stories behind places and the voices of the people experiencing the places in detail enabled an unravelling of diverse perspectives and underlying meanings, which is rarely reflected in most conversations in the direction of urban space yet. To study and to understand the underlying context-specific needs, it is crucial to allow the local community a real voice. “Stories are also considered a catalyst for change” (Sandercock, 2003), the insights gained from these stories demonstrate the great worth of these places.

HOW to build a network and gain people’s trust?

Especially as a non-Tanzanian researcher, building a network, truly immersing in the local environment and gaining trust were the most crucial parts to undertake this people-centred research. The cooperation with and especially the support by CityLab Dar es Salaam made it possible to work closely with the locals. Prior to the research for this article, CityLab had already conducted work in Tandale and the surrounding neighbourhoods (Have a look at Urban Walk Makumbusho and Tandale - https://www.citylab-dar.ac.tz/blog/urban-walk-4-makumbusho-and-tandale, Claiming Space Visual Competition https://www.citylab-dar.ac.tz/blog/claiming-space-visual-competition-1). Previously gained knowledge could be incorporated, contacts were already established and access to the neighbourhood was ensured for me as an ‘outsider’. Realising this work with its profound findings was only possible through close cooperation between the researcher and CityLab. CityLab coordinator Dr Priscila Izar acted as an external advisor and gave valuable input due to her professional experience in this spatial context.

The support of my research informant Jerry was essential to the feasibility of this study. Observing the area and the chosen sites with him was a fundamental point to gain the residents’ trust. He is a well-known resident in Tandale and further works as a guide for the social tourism group AFRIROOTS (https://www.afriroots.co.tz/dar-tours/). The residents are used to him strolling through the neighbourhood with ‘outsiders’ and know the community will benefit from his work, since part of the tour is to get to know products like coffee and chapati, visit Swahili pharmacies and textile (Kitenge) shops. In that way, the community benefits financially from the tourists consuming local products in a very conscious way.

Jerry not only knows the area very well but introduced me to his home, the people and the life in Tandale. As a person who grew up in Germany, this was an exciting and fundamental way to overcome my own cultural bias. Unceasing critical thinking and reflection of fieldwork, findings, and interpretation of what was seen, heard, and felt have been essential throughout the whole process.

HOW to truly reflect residents’ opinions, needs and aspirations?

To investigate the personal perceptions of the residents, the on-site research phase was conducted for three months, starting in October 2021. The primary data collection was conducted in three stages: (i) field observation, (ii) semi-structured interviews and (iii) photovoices. The use of the three approaches ensured a certain validity of the results, as different types of data balance the different biases of different data material. In this way, the interview results explained and clarified the broader observation findings. So did the use of photovoices, which furthermore allowed me to reach a wider scope of people and places. This so-called data triangulation and the focus on storytelling methods derived from participatory approaches helped gaining insights into personal perceptions outside of the westernised framework and understanding of cities.

On-site interviews were carried out with the support of two local research assistants, meaning interviews could be held in the residents’ mother tongue Swahili. For sites mainly occupied by women, a female research assistant conducted the interviews, which seemed to make the interviewees feel more comfortable. Further, all interviews were held on-site while people were using the space. It allowed the interviewees to give lively examples and explain emerging processes and activities while they were occurring.

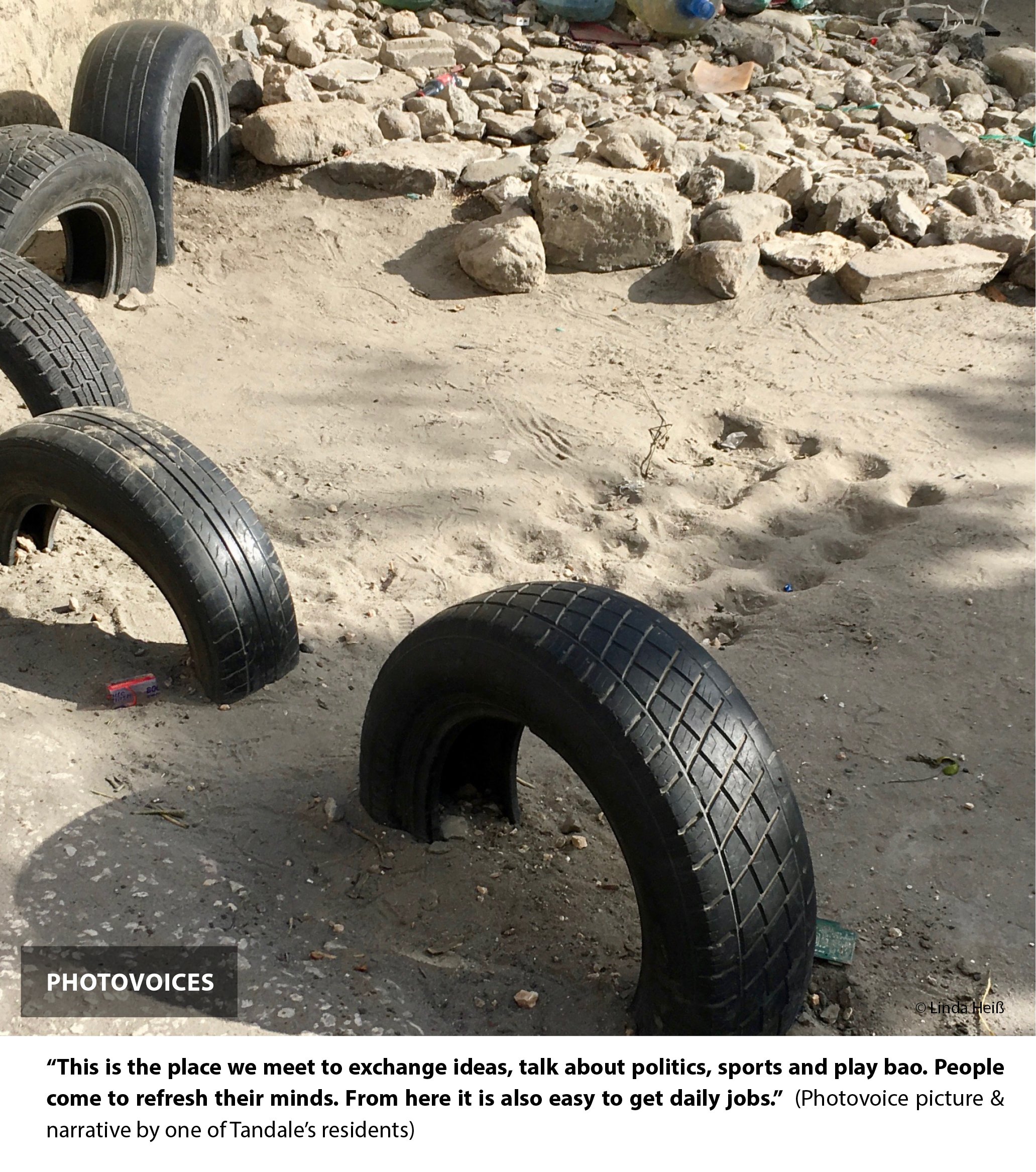

The photovoice approach is a social science method that emphasises social justice and is often used in participatory processes. Explained in a nutshell, participants receive a camera, take pictures according to the explored topic and give the researcher a short narrative of the captured scene. It enables raising people’s voices, especially marginalized groups like children, homeless or illiterate people. It can show daily realities to a wide audience and “literally show the places where the eyes of artists and social scientists cannot go” (McLees, 2013). This methodology is both a form of art and a way to record facts. It can describe realities, show diverse perspectives, and raise awareness.

This approach turned out to be the key method to identifying unexpected issues. It was not about asking the right questions, but leaving room for any kind of topic or place that the participants found relevant to emerge. Through this approach, the ‘selection’ of public usable spaces was not determined by me, the researcher, but by the residents. It enabled me to study places that might often be overlooked but clearly are very important to the residents. More importantly, the residents of Tandale were not only part of the research, but also became researchers themselves. This method “provides multiple ways for experience to be expressed and understood“ (McLees, 2013) and gave insights into daily realities and places where the eyes and thoughts of a foreign researcher like me would have never gone.

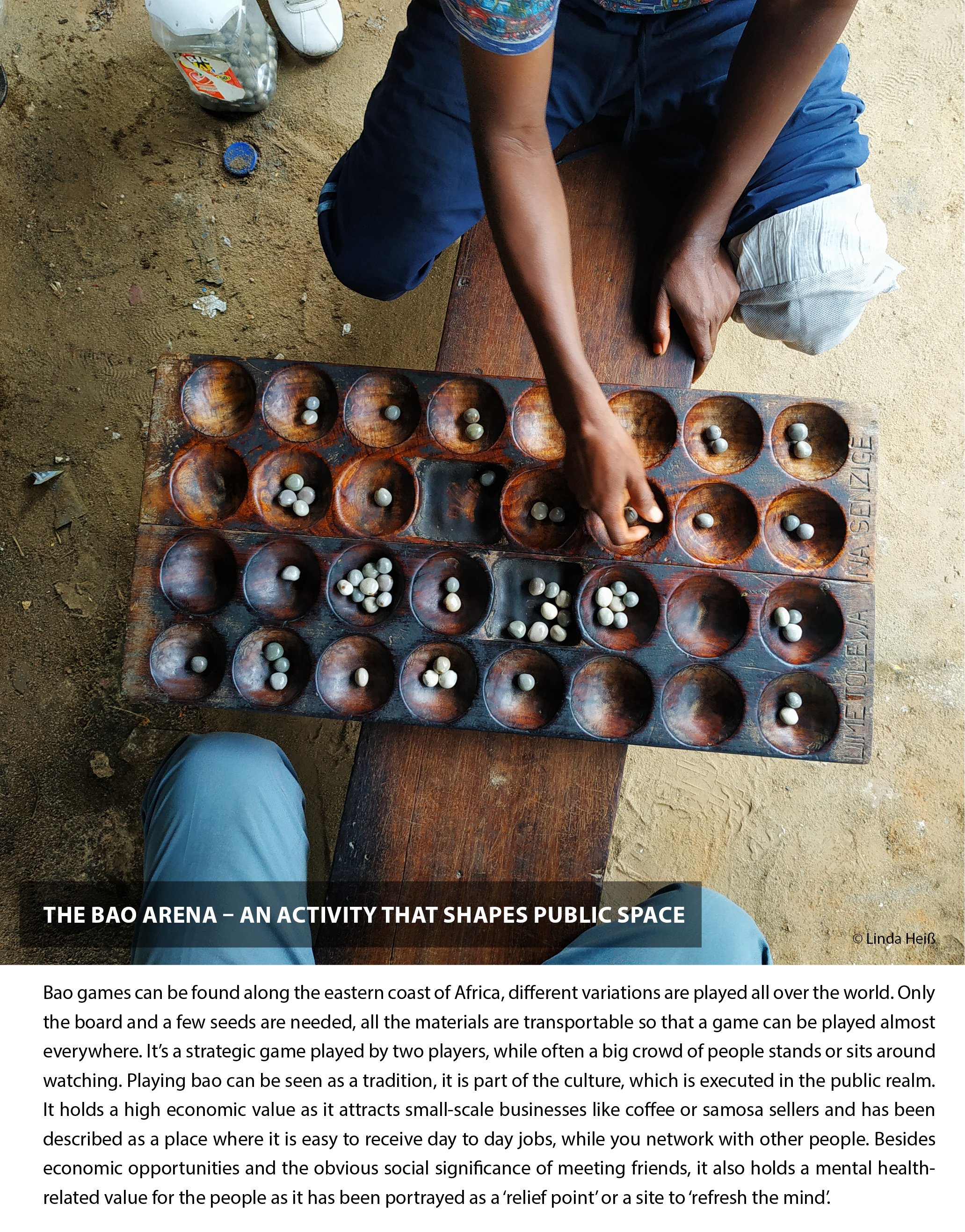

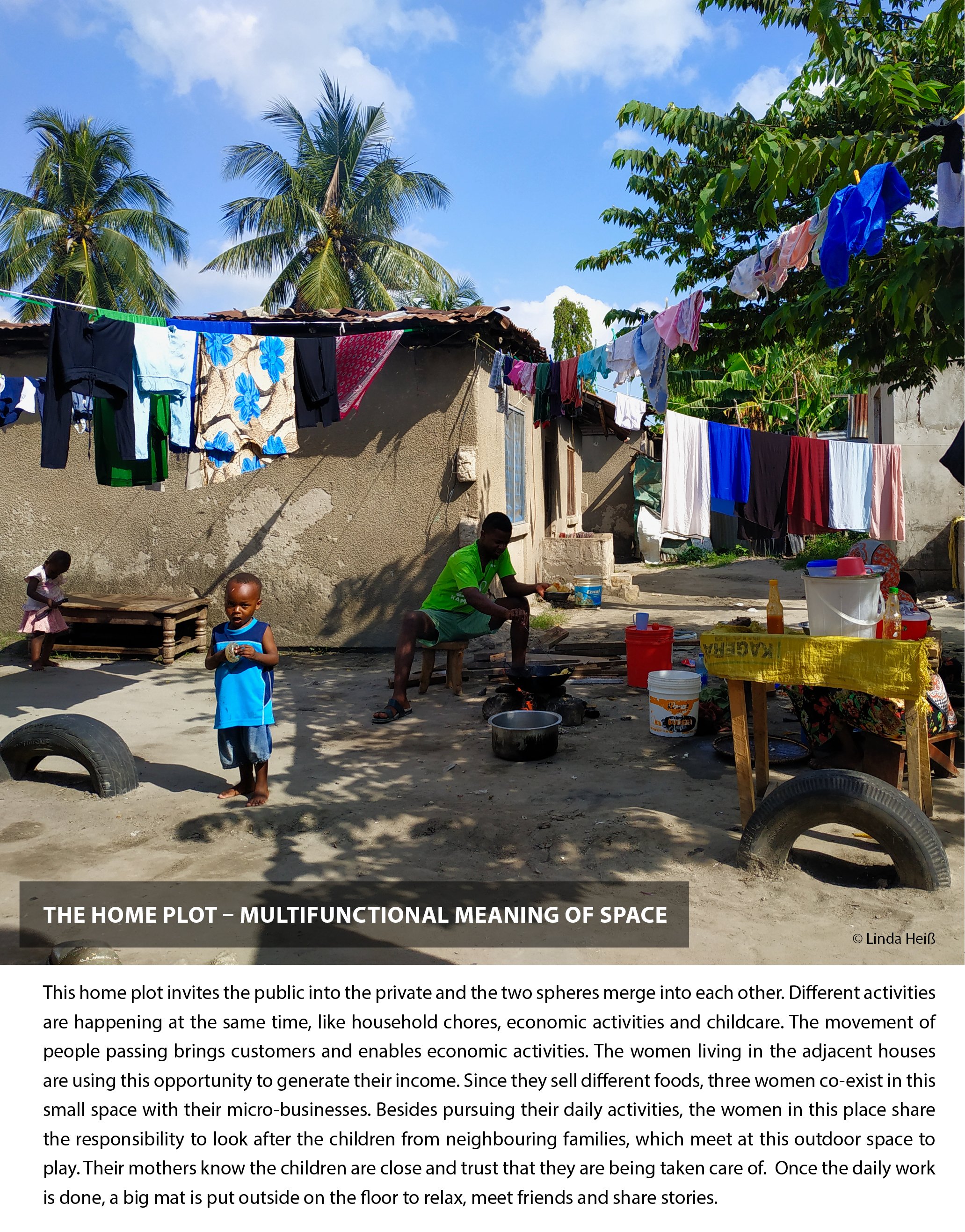

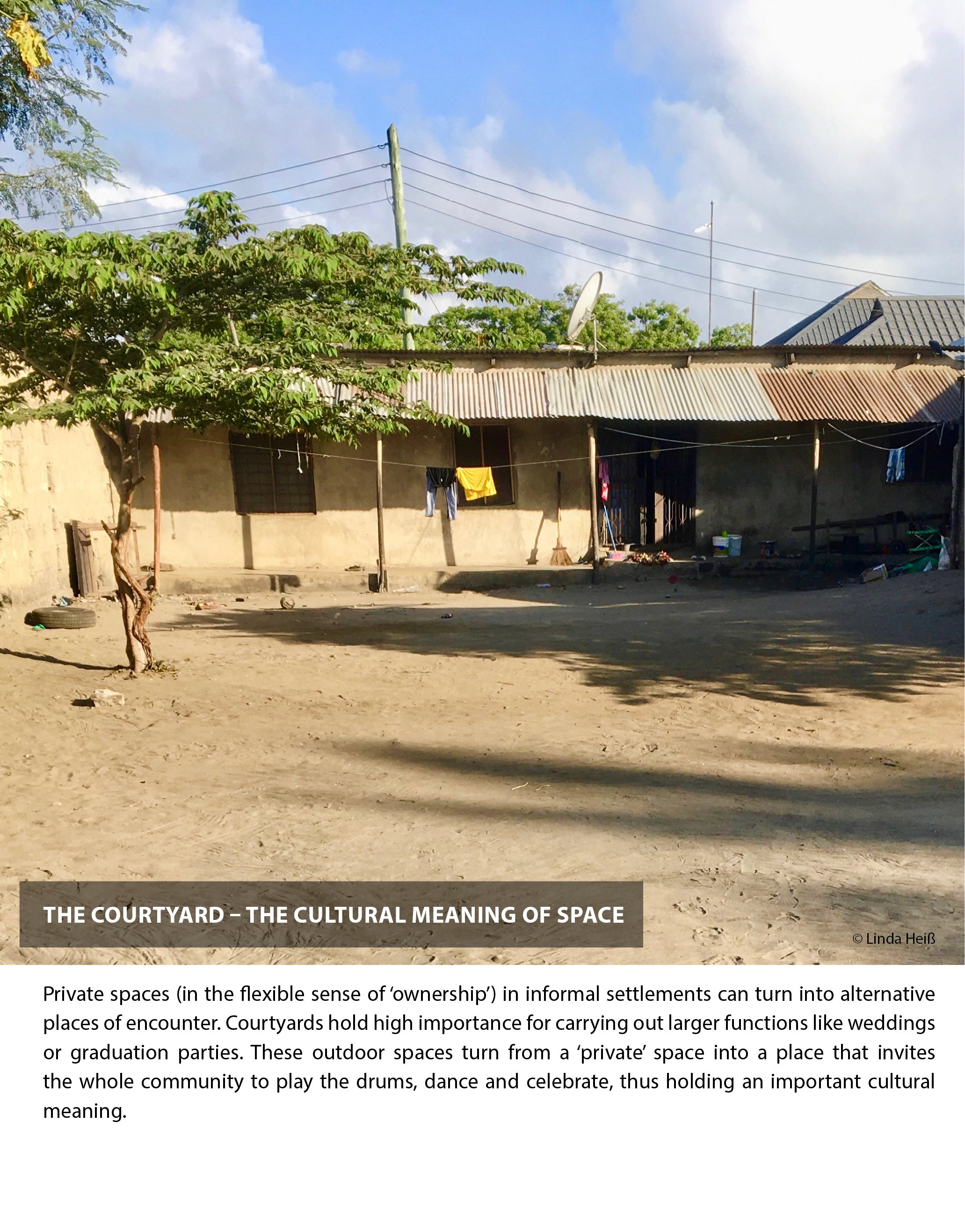

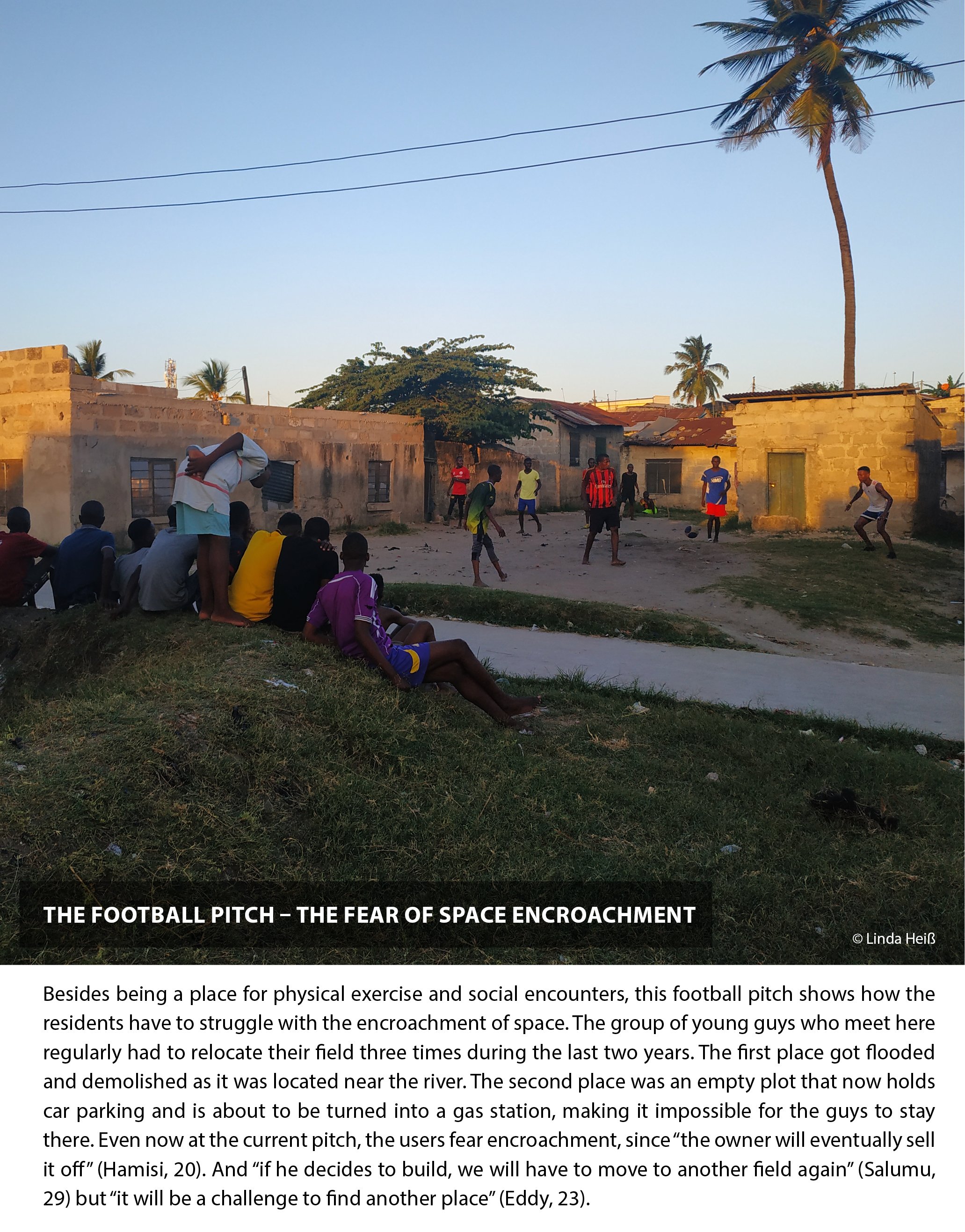

WHAT did story-telling unravel about Tandale’s public usable spaces?

With great input from the residents, the study shows a wide range of public usable spaces (without claiming to reveal a full list). It is through these everyday places, the residents get the chance to share stories, interests, resources, and opportunities. Their multi-layered meanings in social, economic, environmental, cultural and health-related spheres contribute to people’s quality of life.

The study shows that more attention should be given to storytelling methods and the co-creation of space in research and planning. Understanding unique values and individual and collective attitudes can help design projects that fit the context. Tangible and non-tangible layers of space can only be understood through an integrated research approach and in-depth interaction with residents. To comprehend the significance of space, storytelling should occur before any development projects. It could help us formulate plans and policies that actually reflect people’s stories, needs and aspirations more seriously. Let’s make more use of tools like photovoices and offer a platform for people’s voices to be heard!

* The term public USABLE space signifies a connotation detached from ownership and (legal) boundaries. The focus does not lie on the question of “who owns the space?”, but on “who uses the space?”.

** Linda Heiß is an urban practitioner passionate about the co-production of green, creative and healthy spaces for liveable cities. She holds a B.A. in Architecture (from HTWG Konstanz & Escola da Cidade, São Paulo) and an M.Sc. in Integrated Urbanism & Sustainable Design from the University of Stuttgart. Her curiosity for languages and diverse cultures has led her to live in different places around the world. In Tanzania, she experienced life on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam, in the city’s bustling heart, as well as rural village life at Lake Tanganyika. Her interest lies in participatory story-telling methodologies in urban research and practice. Currently, she supports the International Development Cooperation of the German Federal Government (GIZ) in an integrated programme called “Dialogues for Urban Change” while she balances her life between vibrant city life in Berlin and back-to-nature hikes in the German alps.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cilliers, E. J., Timmermans, W., van den Goorbergh, F., & Slijkhuis, J. S. A. (2015). The Story Behind the Place: Creating Urban Spaces That Enhance Quality of Life. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 10(4), 589–598. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11482-014-9336-0

McLees, L. (2013). A Postcolonial Approach to Urban Studies: Interviews, Mental Maps, and Photo Voices on the Urban Farms of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Professional Geographer, 65(2), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2012 .679449

Watson, V. (2003). Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Planning Theory and Practice, 4(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000146318